Human Law and Divine Law (Reflections on a Recent Manifesto)

Bernard Aspe

Next month, Semiotext(e) will release Robert Hurley’s translation of the anonymous Conspiracist Manifesto. First published in January 2022 with the French publishing house Seuil, the text immediately sparked heated controversy. In anticipation of its arrival in English, we have translated a critical analysis of the work by French philosopher Bernard Aspe, who explores its core themes such as the nature of the soul, the biopolitics of COVID-19, and the political presuppositions of struggle. Highlighting both the strengths and shortcomings of the text, as well as the willful misunderstandings that allowed hasty critics to pigeon-hole it as “fascist,” Aspe’s review offers a serious yet balanced evaluation of a book whose infamy is indisputable yet whose meaning has yet to be settled.

Other languages: Français, Deutsch

Such is the paradox of the biopolitical state: it’s supposed to have the goal of ensuring our health, but in reality it makes us sick. —Boris Groys, Philosophy of Care

The Conspiracist Manifesto offers an analysis of the series of power operations underway since the beginning of the Covid-19 epidemic. The thesis it defends is that the coherence of these operations is intelligible only if one understands that the soul is what is at issue. According to Foucault, when we speak of the soul we mustn’t say that it doesn’t exist; it’s a matter of seeing how it is continually being fabricated.1 The so-called “health crisis” has made it possible for a threshold to be crossed in that fabrication (section 1). This being the case, the essential question, of course, is how we ought to respond to it. But for this, we need to know where to set out from, we need a vantage point from which to survey and understand the transformations unfolding before our eyes (section 2). This will allow us to revisit the discussions provoked by the publication of this book (sections 3 and 4) and try to shift their center of gravity (section 5).

1. The Fabricated Soul

To make the soul the central concern of political life is not an obvious move. On this point, we ought to recall Margaret Thatcher’s startling declaration: “Economics are the method; the object is to change the soul” (quoted on p.324). The famous “race for profit” is not an end, but a means. For the class of capitalists what matters is to maintain the initiative, at all costs. And to maintain the initiative, one needs to control the souls of the economic subjects.

Thanks to the work of Foucault, relayed in this regard by Grégoire Chamayou in particular, we have a better handle on how neoliberal thought enabled the extraordinary development of all the processes that sever beings from their relational milieu and lash them to the structures fabricated by the militants of capital. It’s not a question (or not primarily or essentially) of forcing subjects to act, but rather of guiding them to act, of gently leading them to make free decisions that correspond (as if by miracle) to choices that optimally serve the governing elites. And for this, the individual’s milieu or life environment must be configured in the right way.2

The Manifesto develops these analyses further by highlighting three types of operators that are essential for achieving this configuration, and for strengthening its grip in view of the current situation: technological, epistemological, and psychological operators.

If we accept that the soul is immaterial, then we must envisage technologies that make it possible to act upon the immaterial through material means. Situated upstream from ourselves, such materialities will be so well integrated into our actions and gestures that they are no longer perceived for what they are, since they are designed precisely to go unnoticed. The function of infrastructure is to fabricate the life environment of subjects upstream from what they can consciously apprehend. What we witnessed in the crisis management of 2020 was the extent to which this social shaping serves a political function:

A snap of the fingers would have sufficed, it would have been enough that a handful of perverts holed-up at the Elysée declared ‘war’ to realize our condition: we were living in a trap, one which had long remained open, but could spring shut at any time. The power that held us was incarnated much less in the hysterical clowns who people the political stage, to our greater distraction, than in the very structure of the metropolis, in the supply chain on which our survival hangs, in the urban panopticon, in all the electronic snitches that serve us and surround us — that is, in the architecture of our lives. (192)

In addition to the invisible materiality of these infrastructures, there is the immateriality of what is held to be true. That epistemology is not an academic area of university philosophy but a major terrain of political struggle is something we act like we’ve known for a long time, but no longer really bother to examine. Yet this helps to explain why conspiracy theory (let’s say that of QAnon or Trump) is so hard-headed about science. The source of the problem might lie in the idea, now widespread, that “the division between reality and illusion, the distinction between truth and untruth, is now obsolete,” or that “the real doesn’t exist,” that “reality is invented” (184 | 178).

However, fabricating reality doesn’t just involve a series of performative statements or theoretical constructs, but also a set of techniques of government. The latter are attached to an overall vision of the world envisioned as an ensemble of quantifiable positivities. “Object-oriented ontology” was able to kindle the hope of transcending the human, but it turned out to be the symptom of a world that increasingly resembles its description, not because the sciences would be more and more attuned to the world, but because they make it possible to produce the object that corresponds to their description. The most ramified techniques of government are rooted in this power conferred upon the sciences to generate the world that they know.

The notion that reality is produced by a scientific approach intent on knowing it is especially true when the thing to be produced is human behavior. Here, epistemology and psychology merge, or at least become inextricable. There is a “social engineering” that goes by way of the behavioral sciences in particular (161). A NATO report stresses the “cognitive domain” that transversalizes all the others (108 sq.), while another report, this time from the CIA, underscores the importance of “the battle for men’s minds” (112). In each case, the idea that power operates through the manipulation of minds was plainly spelled out during the Cold War period. The thesis of the Manifesto is that this project did not end with the fall of the Soviet Union, that it continued to develop and amplify up to the present. During the Cold War, it was a question of producing the liberal democratic subject as a counter-model to the subject of the totalitarian world (144 sq.). Nowadays it’s a matter of producing a subject adapted to the obedience requisite of a period in which instabilities are bound to increase, particularly if one intends to control the effects of these instabilities and prevent them from terminating in the overthrow of technocratic domination.3 That the cold war has returned so pressingly to the agenda with the war in Ukraine confirms that we were far from even beginning to free ourselves from this project.

To bring this evocation of the book’s theses to a close, I’ll just mention two examples of operative theories that enable the conduct of human beings to be conducted. First, there is the thesis proposed by Kiesler in his Psychology of Commitment (1971), which so clearly demonstrated its efficacy during the health crisis, according to which discourse follows action:

The anthropological hypothesis of Kiesler and of all social psychology is that humans don’t act in accordance with what they think and say. Their consciousness and their discourse serve solely to justify a posteriori the acts they have already completed. (164)

One need only ensure that decisions are made in a state of urgency (wearing a mask outdoors, no longer shaking hands with a friend, getting vaccinated), and the subjects of these decisions will be led to rationalize them retrospectively.

The second example is “the effort to drive the other person crazy,” which operates by inducing “an affective conflict” in him, by “undermining his confidence in the reliability of his own emotional reactions and his own perception of external reality,” as Harold Searles writes (quoted on 173-174). This is exactly what we experienced: “Who can claim that, for two years, we have not been systematically subjected to a succession of fear stimuli aimed at generating a state of docile regression, to a methodical shrinking of our world, to contradictory injunctions designed to make us suggestible” (170). If, according to the current data of the WHO, cases of depression and anxiety increased by 25% worldwide during the health crisis, this is not only because of fear of the virus, but at least as much because of all the restrictions that displayed no concern for the mental fragilities of human beings, and which resulted in a gigantic “gaslighting” (in reference to Cukor’s magnificent film, Gaslight) that generalized the disposition to doubt oneself. From this point of view, one can’t help but feel grateful toward a text that has enabled some of its readers not to remain confined within a devastating solitude.

2. The Point of View

Let us now consider the position from which the book speaks. Understanding what the term “soul” signifies depends upon an ethical perception. We will understand nothing of this Manifesto if we don’t first try to nurture and maintain a perspective or point of view which those responsible for the run of things wish to sweep away. We can say that this is the book’s ethical point of view, with the qualification that the authors have no interest in defining it, believing that, as Wittgenstein once taught, it’s best to avoid any ethical theory. For, according to him, if there is one inclination of thought that must be rejected it is definitely the inclination to propose such a theory, conceived as a structured set of propositions strung together in good order. Not because such a theory would inevitably be dogmatic, but rather because it would consign its own principles to the contingency of reasonings and argumentations, which naturally could be countered by other reasonings and argumentations.

A century before Wittgenstein’s remarks, one finds a similar condemnation of ethical theory in Hegel’s The Phenomenology of Spirit, at the very end of chapter 4 (a key moment involving the passage from an examination of the forms of self-consciousness to that of the forms of Spirit). What Hegel here calls ethical substance is recognized as such, or more exactly it can animate our experience only provided it is not consigned to the contingency of demonstrations, but is borne as a set of truths that cannot be placed in doubt. The authors of the Manifesto might speak here of a set of ethical certainties that need not be put into formulas, but are presupposed. In their view, it is the expression of these presupposed certainties in effective practice that should be regarded as the only consistency of a living community.

To be sure, ethical substance (as it’s called) is only a stage in Hegel’s movement of thought: to become fully moral, the community will first have to dialecticize (that is, overcome) the opposition between human law and divine law — this is the beginning of chapter 5, where the opposition between Creon and Antigone is evoked. Ethical substance remains attached to divine law, and Antigone is its militant. Let’s set aside Hegel’s dialectical optimism and consider the present situation from the angle that its description seems to us to suggest, but that Hegel prefers not to envisage: the opposition between human law and divine law is now irreversibly set, and is no longer dialecticizable. On the one hand, there are the citizens who abide by the prescriptions supplied by the lawmakers, that is, by the written laws, assumed to be turned towards the universal, but which happen to enable the fabrication in each subject of a soul adjusted to the ongoing mutations of the world of capital. On the other side are all those who remain attached to the unwritten divine law, which doesn’t need to be formulated and demonstrated. On one hand, the law promulgated by the governing authorities and more generally the masters of the economy-world; and on the other, the underground law, which, as in the case of Antigone, continues to bind one to the Earth and the living beings of the past.

This detour through the piety of Antigone (a figure that may well have been recalled by those who, especially in the first weeks of the pandemic, were not able to bury their deceased) might seem to favor a strategy of disqualification aimed at rejecting the “mysticism” of the Manifesto — as does perhaps the allusion to an ethical substance at a time when everyone is supposed to have accepted the unsurpassable deconstruction of all substance. But before exploring our disagreements, in what follows (sections 2 and 3) we should first try to get a better handle on the viewpoint of this book and its insistent demand that we position ourselves firmly against the law of the new order of the globalized world — which is meant to serve us as a universal.

Let it be said once and for all that the term “law” here, in the expression “human law,” is an image: in it, we must see lumped together not only formal statutes, or rather the countless decrees of governments, but also the scientific or media prescriptions and the models of behavior they promote. All ethical consistency, in the sense the authors give to the word and thus, because for them it’s the same thing (we’ll come back to this), all political consistency, can be radically constructed only outside the law in this broader sense. “Divine law” as well is thus an image that derives from the forms discovered by a community, and capable of existing outside of the recognized law, to maintain and invent an experience of living which that official law, or “human law,” strives to eclipse. Divine law is an unformulated law, a law that bears no relation to the form of the Law, and that moves from within the assembled living beings who recognize it, not as a set of prescriptions, but as a collection of shared acts and gestures.

The point of view of the Manifesto is therefore that of a community of refusal attached to a single ethical substance, one which remains tacit and which is, at least partially, incapable of formulation, and whose stateable principles don’t exactly coincide with the reasons (the ethical certainties) that lead one to belong to it. To give this ethical community, this “ethical we,” its consistency, it’s necessary to rediscover or constitute a soul that doesn’t allow itself to be fabricated by the global law — the law of the global world. And for that, one needs to maintain a relation with divine law, but of a divinity that would remain immanent in the world, without being confused with that ersatz theological horizon which is health. “The pursuit of health has supplanted that of salvation, in a world that no longer promises any salvation. It’s just that, while the Christian faith has fallen by the wayside, the perception that ‘there are also gods here below,’ as Heraclitus said, hasn’t gained any ground for all that” (223). Henceforth, it’s a question of creating room for this perception of a non-religious divine, with a shareable fullness of life not based on any transcendence, to gain ground. A divine, therefore, that is no longer that of a world projected beyond life, but the form this shared life can give itself in its full blossoming, which it can attain as soon as one stops confusing it with the object of scientific knowledge, and medical science in particular, or with the object of governmental management.

We can agree, then, that in order to begin, it is necessary to avoid being among “those who submit to all the norms newly invented out of nowhere in the hope of a ‘return to normal’ which, for that very reason, will never come” (39). Indeed; the new human law prevents one from taking seriously any idea of a return to normality, even though the health or vaccination passes are suspended for a time. The arsenal of exception fabricated on the occasion of this pandemic will henceforth be readily available, and won’t fail to be reactivated for managing the pandemics to come (Covid, flu, new diseases, or ones whose way of spreading seems new, like monkeypox), and other catastrophes that lie ahead. Yet if the new law is already extending its authority into the future it is preparing for us, we must see that it has also plunged its roots into the past. Even if there has certainly been something new in this crisis, the present situation did not arise from the emergency management of an unforeseeable event.

According to the authors of the Manifesto, even if it may not have given rise to a consultative framework drawing the governing authorities together (but it’s enough that the latter were trained to defend the same logic — and this is the sense in which they conspire (32)), this management should be understood above all as the response to the movements that marked the end of the 2010s, of which the Yellow Vests are the emblem in France but which also surged forth in Hong Kong, in Catalonia, in Chile, in Lebanon, in Iraq, and in Colombia (88-94). These movements sketch out a community of refusal which, in order to become one in spirit, must find their own way of manifesting as such (to themselves first of all).

But the whole question is first how to give substance to this community, or rather, perhaps the authors would say, how to ensure that it finds its plane of consistency. Whether it has succeeded or not, the book has sought to be an activator [opérateur] allowing such a plane to be established. To make an intervention in the form of a book into a political activator is to suppose that a certain type of enunciation4 would be able to actualize what it lays out, at least what it convokes as a “real potential”: the unity, and hence the augmented force of this community of refusal.

3. The Question of Style

Here we come up against the first objection that managed to be formulated in the course of the critiques, most of them very hostile to the text, but generally uninterested in assessing the project as a whole. This objection concerns precisely this desire to find a form of messianic enunciation, which creates a blockage for a number of readers. An enunciation that would cause one to trace too sharp a line of demarcation between the weak who submit and the strong who refuse submission; further, these strong ones would be strong only because they have the luxury of choosing to withdraw from the apparatuses of power. In this way, the messianic enunciation would serve to support an aristocratic position, and only from this position can one remain indifferent to the lot of the weak. This would be proved by the fact that the book has not sufficiently underscored the fate of persons having suffered the full effects of the most criminal management policies, the slum dwellers of Modi’s India and the inhabitants of the favelas of Bolsonaro’s Brazil. The messianic enunciation, then, would suppose a line of division clearly separating those who submit and those who do not, but at the same time, those who know and those who don’t know, or don’t want to know. The rejection of this enunciation went on to focus almost exclusively on the style of the work — a style seen as dogmatic because it stated propositions without demonstrating them, without supporting them with arguments. So we should return to the questions outlined above from the angle of epistemology, starting once more from this question of “point of view” — that is, from what the authors would prefer not to call “subjectivity,” but which could be labeled in that way at least to indicate that it’s a matter of distancing ourselves from the prevailing objectivism.

On this point, any “free spirit,” in the sense that Nietzsche sometimes gave to the term, could not help but side with this Manifesto, at a time when it seems harder every day, for a readership that has learned the notion of “seriousness” at the university, to accept a work that cites its references only partially, that presumes to speak athwart supposedly distinct “domains” (politics, sociology, psychology) and that doesn’t bother to demonstrate the things it posits. An approach that completely contravenes what has asserted itself as “the spontaneous philosophy of scientists,” what the authors of the Manifesto call positivism, something that goes far beyond the philosophical current which generally goes by that name. In fact, one can call “positivist” the posture of any intellectual whose main concern is to preserve the recognition of their peers, well beyond the “hard” sciences alone. We have seen this phenomenon throughout this whole period, when a great many “committed” intellectuals less than courageously absented themselves from all polemics, when they even showed a rather grotesque faint-heartedness at the idea of being associated in any way with those suggesting a reading of political operations that might be deemed unacceptable. And even among those who have long claimed to be deconstructing positivism, even in the circles of the most constructivist thought, the followers of Stengers and Latour also abstained from any risky position-taking, even though the situation seemed to lend itself splendidly to the application of their problematics and their methods (examination of scientific controversies, the way they’re constructed, what they exclude, the place of science in public debate, etc.).

But maybe this is not a chance thing, maybe constructivism, even “speculative” constructivism, is basically just a variant of positivism. Because neither the rigid positivists nor the subtle constructivists have ever begun to understand what the very concept of politics might signify; so they seem blind to any relation between politics and truth. Mario Tronti has insisted on it for decades: the partiality of political knowledge isn’t what forms an obstacle to its truth — on the contrary, it is its precondition. For example, to understand the capitalist world in the 1960s means adopting the workers’ point of view, which would never have been able to coincide with that of the bosses. The same goes for any “great politics”: “one constructs a great political culture only on the basis of a collective self, from a non-individual partial point of view, from a point, or several points of contrast between two parts of the world, two kinds of human beings, two social presences, two visions of the future”5. The image employed here of the human law/divine law duality is a way of extending this observation.

But it has become very difficult, for many people in the thinking professions, to fully assume this true partiality. Whence no doubt the state of panic, both muted and speechless, among the intellectuals, with rare exceptions. There is indeed something unacceptable in what is imposing itself currently through crisis management; but if one ventures for example to contest the recommendations of the WHO without being a doctor or epidemiologist (or sometimes even being that), one may be suspected of not understanding the reasons of science, and of seeing the positions one takes refuted by the facts — whereas the university has trained us to avoid such a test. To ward off this specter, we learn that it’s best simply to steer clear of the fray.

But beyond the ordinary cowardice of academics and “radical” thinkers anxious to preserve their standing, one had to note that there was a problem in the pursuit of truth. It is in fact a problem of an epistemological sort which was posed to the academics themselves, who “because of competitive specialization, because of knowing all there is to know about next to nothing, their knowledge doesn’t have any possible use” (104). But within every family (including radical families) we cannot help but note with alarm the extraordinary reversibility of arguments. Once this stupefaction has passed, we usually try to gloss over the observation, and redouble our self-assurance by holding firm with one side of its denial — for example: “the illness is not all that serious,” as opposed to “there are no side effects of the vaccination.” The Manifesto sometimes tends toward the first denial, perhaps in response to those who exaggerated the second. In any case, this dual exaggeration distorts the clear perception we should construct of the situation, which would spare us from the false debates that it occasions, from the way they make us lose time, energy, and sometimes friendships.

Our feeling of astonishment at the depth of this confusion in the relation to truth is no doubt a function of how clearly we were able to see, after this “crisis” was declared, that the scientific approach — thought to incarnate, and it alone, the function of truth-telling — was not able to provide what was demanded of it. As the Manifesto emphasizes, we were finally able to glimpse the ordinary operation of science, beyond the constructivist circles. We realized that scientific truths are strictly local, that they depend on the definition of their object and on their fields of study, which are necessarily restricted; and we saw that the diversity of their very ways of questioning this or that object in a given field of study can lead to incompatible descriptions. All this became patently clear, and yet we avoided drawing the necessary conclusion: our societies (and even more so our political communities) suffer from having entrusted the entirety of truth-telling to the scientific approach; and thus from having to repress the idea that to understand a historical and political situation as a whole, a scientific approach does not suffice — and at best can only offer scattered materials.

In order to understand a political situation, it’s necessary to have a political point of view, which is never reducible to what objective knowledge (the necessarily dispersed, untotalizable sum of various kinds of objective knowledge) might say about it. The very fact of causing this non-scientific point of view to disappear in the search for the truth of the situation is itself a victory for our adversary; and this is in no way an accident, for its political aim is precisely to make the political space disappear as such.

There is a difficulty, however: the fact that the authorities, for example in France, did not actually follow the recommendations of the scientists has often been underscored. So one mustn't postulate a unity between political power and scientific veridiction — and then it is precisely a matter of explaining how the reference to science has functioned, on the one hand, and on the other what logic power has followed in most countries (I return to this in section 4). That power obeys its own logic, which doesn’t stem from its scrupulous adherence to scientific statements, is one thing. That it uses the weight given to these statements in our societies to disqualify any other type of discourse is something different. One is not asking any excessive intellectual gymnastics from a reader by telling them that power has, in France and elsewhere, appealed to the indisputable eminence of scientific discourse in the treatment of illness in order to disqualify potential adversaries, precisely to secure the political space exclusively for itself, precisely to conduct its politics which, once the contestation is extinguished, could very well, or will in fact follow a different logic than that of the WHO or scientific counsel. In power’s games, the function of science is not to dictate what needs to be done, but to silence what is not scientific.

For there to be a political existence, it is first necessary that all that exists, or that is, is not reducible to what sciences may say about it. According to the authors of the Manifesto, the victory of the enemy, with its effort to make political truth disappear, stems from the way the life sciences have conceived of life, an essential cog of the inscription of the living in the space of biopolitical governmentality. Perhaps the heterodox approaches existing within the biological sciences themselves should have been evoked, but one can agree in any case that it is indeed the monopoly on truth granted to the sciences that ended up imposing the “molecular vision of life” (290) to a very large extent, according to which each being must be considered as a stock of quantifiable physico-chemical reactions. The advantage of considering beings in this way is that they become perfectly malleable. Manipulating human beings with the same science as that which enables one to manipulate particles and genes or to program spaceships is the project of contemporary biopolitics, stated as such in the documents cited all throughout the pages of the Manifesto.

4. The Question of the Dead

The social function assigned to scientific discourse in our societies is therefore a central element of biopolitical power. As to the description of this biopower, what is said in this book will be rather familiar to readers of Foucault and Agamben, two authors who have constructed a rich intelligibility of the way life has been inscribed in the apparatuses of power, and thus have illuminated the political stakes of this inscription. If one takes the trouble to read or reread Foucault, one sees that the concept of “biopolitics” has clearly always designated the concern for life insofar as it enables the increase of wealth. “Biopolitics” has never named anything other than the inscription of life within the horizon of economic development. The health of populations, as well as that of individuals, have become major preoccupations for two and a half centuries only to the extent that they can be essential cogs of that development. The fact of being able to let die those who don’t serve that function, or even of sending them off to die in warfare, never contradicted the “concern for the health” of populations (226). In a general way, biopolitical management is structurally confronted with the necessary triage between the life that is worthy of being lived and the life that isn’t.6

On this point, however, we need to pause again and consider the most virulent criticism addressed to the writers of the Manifesto, accused of adopting the biopolitical point of view which they set out to critique, or of themselves becoming the proponents of a new eugenics. They were charged for example with being indifferent to the Covid fatalities, because they barely mentioned them. But one could reply that here again it’s a question of “style.” The authors were wrong to give the impression that they minimize the effects of the illness, but they would likely reply on this particular point that if they don’t deal directly with the deaths from Covid, it’s not that they deny that reality; it’s that they refuse to adopt the customary caveat which has become a tacit rule: talking about the health crisis is possible only if you begin by citing the number of fatalities, and more broadly the number of persons struck by the illness.

If it is permitted to refuse this caveat, it’s because what is essential here has to do with the saying, l’énonciation, and not with what is said, l’énoncé. To say that the illness is serious, to show that one knows the data, is to validate the obligation which the data are supposed to contain. An obligation that doesn’t actually concern the deceased (no need to show that one deplores them to be saddened by their passing), but that requires one to display one’s belonging to the clan of the enlightened, far removed from the murky conspiratorial milieus. To refuse to submit to this obligation, on the other hand, is not to adopt a eugenicist point of view (“nevermind the weak, the old, the sick…”), it’s to refuse to consider that other deaths, or other persons seriously compromised, mentally or physically, count less, even if they are less numerous: those who couldn’t cope with the loneliness or the impossibility of realizing the convictions they held in their heart, those who couldn’t be treated because they suffered from something else, or those who couldn’t bear the vaccinal experimentation, among other examples.

The background objection always comes down to associating this book with a fascist politics, and in fact the book’s perspective seems to be approved by the extreme right (Soral wrote a review of it, which is as worthless as everything else he’s written), which would show, regardless of the authors’ intentions, that it is compatible with that political posture. A problem all the more acute as it has gained an added relevance in the light of recent popular eruptions — think of the Yellow Vests, the movement against the health pass, or the freedom convoys. One has to grant the extreme right one merit: that of continuing to draw dividing lines, whereas the tradition of the left has continued for several decades to blur them, or even conjure them away. The problem is that its leaders draw this line by gathering up the worst aspects in diffuse subjective dispositions: racism, machismo, transphobia, “rural’ traditions, etc. They count exclusively upon forces of reaction that will lead us even faster to the abyss than those of a Macronism as smooth as it is criminal. They prevent themselves from seeing for example the way in which feminism and more generally the attempts to overcome the binarity of the genders can constitute a fertile matrix of political subjectivation for the new generations.

When we consider the intelligence deployed in these pages, it is safe to assume that the operation of the Manifesto is not meant for the impaired brains of the “thinkers” of the extreme right, but for the construction of a space of thought capable of replacing the one they occupy, enabling the authors to address the participants in the aforementioned movements (Yellow Vests, etc.). To do this, the correct line of division must be drawn: not one that carves-out an identity-based “we” by demarcating it from figures of otherness (migrants, trans, etc), but a line that separates a political “we” from those responsible for the planetary disaster — let’s say the class of technocapitalists and their servants, all those who spearheaded the initiatives that led us to this disaster. If there is a discussion about the Manifesto that we need to have, it concerns the drawing of this line, for this is indeed the central issue (section 5).

The objections I’ve spoken of were enough to fill up a few rageful reviews, whose principal effect was to block out any real discussion of the issues, which depends upon a clear identification of the two enemy camps. If we’re to contribute to that twofold identification, we need to return to the political logic that motivated the decisions of the governing authorities, who, once again, are far from having systematically followed the scientific recommendations. A logic that was apparently fractured, divided, and disparate from country to country, and yet relatively unified in reality.

Karl Heinz Roth, a former theorist of autonomy, who is both a doctor and a historian, has recently written an analysis of the management of the health crisis.7 His arguments are comparable to certain ideas defended in France by Barbara Stiegler, from a different political point of view but they sometimes converge with the analyses of the Manifesto, for example concerning the role of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in the programs of research on pandemics. It appears that this role was mainly to promote the idea of a crisis management based on the “worst-case scenario,” one which was followed in the management of this crisis, but which did not correspond to the actual form of the pandemic. Roth speaks of an illness “of moderate severity” (subject to new mutations that are always possible), which is in no way a provocation but according to him the appropriate classification, in terms of public health, for an illness transmitted by a virus effectively more serious than the standard seasonal flu, but which, with about half of the persons asymptomatic, called for a targeted treatment: the persons most exposed could have benefited from a specific protection — which would have also better enabled the accommodation of severe cases developed in persons not identified as being “at risk.” The important thing, however, doesn’t reside in the classification itself but in this paradox: in this situation, adoption of the “worst-case” scenario did not result, as one might think, in more effective treatments; quite the contrary.

The masters of the world, after having proven their entitlement as such by confining the near-totality of the world population, intended to combine this worst-case scenario with maintenance of the neoliberal “gains” in the management of medical institutions. In his interview, Roth explains that, after consulting the various plans for combating the pandemic in different countries, he came to the realization that “these plans were all oriented toward maintaining the necessary political and economic infrastructures, but didn’t propose anything for the health sector.” Whence the perfect aberration inside of which we were compelled to live: on one hand, the spreading of a state of panic justifying the most grotesque emergency measures; on the other, due to the structural deficiency of the medical system, the measures taken to protect the most exposed remained highly inadequate. So it was necessary to name other culprits than the authorities, some scapegoats (those who were called, with a straight face, the “unvaccinated”) and to widen the cleavage thus created in the population owing to the policy of sanitary passes, destined for a great future.

One might find it strange that, only a few months after this hysterization had reached its point of culmination, everyone rushed to accept the official denial of the epidemic. It was found that the large-scale experimentation of the worst-case scenario had (provisionally?) come to an end. The alternative between a well thought-out and “civic” management à l’européenne and the fascist wager of a Trump or Bolsonaro seemed to fade out then. More or less everywhere, one agreed on the need thenceforth to “live with the virus.” The essential task was accomplished: one had succeeded in managing the pandemic while preserving what had been its cause, namely the very politics that is responsible for the generalized degradation of the environments of life (climate disruption, destruction of wild habitats, industrial livestock farming) that was the cause of this pandemic and will cause future ones. And which, quite logically, is also responsible for the disastrous state of the medical institutions. The weirdest thing is that “we,” the good citizens that we were supposed to care about being, have become by a stroke of magic the ones responsible for the good health of the hospital institution. When the vaccination policy showed its limits with respect to the declared project of eradicating the virus, it became a matter of doing the right thing and not overburdening the hospitals (Manifesto, 233-34). Such was the “piece of blackmail around hospital care. Either you comply or the hospital will break down. The swindle does have a certain savor: that a service would be subject to a breakdown at any time is the very definition of its optimal state from the viewpoint of its neoliberal management” (233). It is possible that this blackmail will be mobilized anew in the coming weeks. It’s worth noting that denying the airborne contagiousness of the virus for more than a year, and more broadly, the failure to take into account its circulation via confined air, is also an element of this logic of individual responsibility, because taking this into account should lead logically to halting the overall degradation of our living conditions, but this is precisely what the authorities have managed to avoid up to the present.

However, taking note of the dilapidation of the healthcare infrastructures as a conscious outcome of neoliberal policy should not lead us to take up the defense of the hospital institution as it existed “before.” The writers of the Manifesto remind us with good reason of the essential critiques of that institution, formulated by Foucault in the 1970s, or from another angle by Ivan Illich. Especially seeing that in the situation of crisis these critiques had become unacceptable (“Criticism of the hospital’s near monopoly on medical resources, or even of the essential aberration of that institution, have become so timeworn as to be inaudible”), at the same time that the benevolent attitude toward attempts at care on the part of “parallel” or traditional doctors disappeared: faced with the emergency, it was a matter of being serious. And as everyone knows, being serious is being rational and “positive.”

It would be absurd to say that in such a situation it would have been necessary to desert the hospitals, but it was doubtless essential to take into consideration what was unfolding outside the medical institutions, or on their fringes, and in any case outside state policies. Roth stresses what might be called a form of communized, non-institutional care, through networks of mutual aid, the spontaneous collective forms of solidarity that have developed on a more or less large scale, outside any state framework, in every country. It was not surprising to find these forms in the Zapatista community of Chiapas; it was somewhat surprising to see them spring up in the Brazilian favelas.8 The disdain for such popular forms of mutual aid shown by the governing authorities (with the exception of Japan and Denmark, according to Roth) only worsened the catastrophe.

5. Political Experience

Let’s return to the problem of point of view, that of the community of refusal. “This book is anonymous because it doesn’t belong to anyone; it belongs to a movement of social dissociation that is underway” (22). The problem is that this movement is for the moment disparate, without any unity. I do understand that the authors’ aim is not explicitly to unify it, but rather to amplify it, but the singular here (a movement) is revealing, and seems to restrict one to this alternative: either the a indicates precisely an aim, and one must then ask how the unity can be constructed, since it is not given; or there is indeed a movement, and following the authors, one could think that as such it is the expression of its epoch — or of the coming epoch. Which assumes that the epoch, present or to come, seeks a voice. It seems to me that it’s not the epoch that is the source of this disparate and potentially unified political discourse, it is not the epoch that is speaking. What is speaking are heterogeneous political subjects.

If there can be a voice on our side, if a unity must consequently be not only invoked, but constructed, it must be that of a political process. If it must be sought, this is because it can’t be found by lending an ear. If there is a process, it’s insofar as it involves the composition of heterogeneous elements which are bound to remain such; if there is a unity, it’s that this unity is not something conquered through the erasure, or even the subsumption of the heterogeneous. What we have are heterogeneous forms of political subjectivation.

Let’s bear in mind, however, that the question of dealing with the existing world does not mean, as in Hegel, adapting to the law that structures it. Here one must remain fully on the side of the rebellious Antigone — but an Antigone who would not regret her gesture. The question of composition of the heterogeneous is linked to what remains of divine law, going back to the image offered at the start, that is, to the aim of a life delivered from the abjections and mutilations imposed on it, and thus in irreducible conflict with human law understood as the law of the inner world of global capitalism.

Dealing with what exists means improvising with the disparate forms of refusal, with the disparate ways of envisaging a delivered life in the above sense. It’s true that the authors of the Manifesto acknowledge the plurality of these forms and ways. In the proposition “there are ethical we’s” (257), the plural is essential: one can grant a diversity of forms given to the ethical consistency, a diversity of forms of life. But then the question is twofold: on the one hand, it is how to manifest the compatibility of the heterogeneous. On the other hand, it is how to know if what “commonizes” such differences is the dispersal itself, that is, precisely their plurality with respect to the unity of the global world. If one rejects this second hypothesis, which is rather facile and seldom advanced, and one considers that a true unity must be sought, a unity that would not be said only in the negative, then something has to be added in order to bind and name the common space which these differences compose.

The hypothesis I would submit is that this common space is not defined by an ethical consistency, but by a properly political consistency. In other words, perhaps the right way to think about this is that there needs to be a political space that supplements the ethical consistencies. I’m not saying that the latter are not political, but that they are not the whole substance of the political. In the Manifesto, the ethical substance left to its positivity is thought negatively in relation to the political space which it is abandoning, and that stems from the resistance of ethical propositions to formulation. It’s not this unformulability that I call into question, but the inability of the ethical consistency to delineate by itself the space of a politics responsive to the global situation. Now, the properly political space conceived as a supplementary space would allow us to confer a positivity upon our refusal, that is, it would allow us to wield refusal itself as an affirmation. Not the affirmation of a particular world against that of capital, not simply a collection of heterogeneous worlds against the globalized world, but that of something else than a world: a political aim that has found its strategy. A camaraderie that is added to the ethical friendships.

So the preceding remarks propose a dialectical articulation, but not with “human law,” the law of capital. The political point of view concerning the current situation cannot be solely that of the ethical substance. The political point of view assumes a dialectical articulation with the world as it is, via the plural forms of refusal, and not a radical separation. The Manifesto is not wrong to signal the impasses that can trap the feminist or decolonial movements — an identitarian trap, knowing that plural identities can be, as such, perfect objects of management; knowing also that in these impasses, these movements cause the group superego to proliferate inside militant circles, which is never good news. But it seems difficult to construct a serious political space without the support of all those who, within these movements, and whatever their gender, don’t allow themselves to become ensnared in these traps. For it’s by that means, too, that “ethical we’s” are formed now.

Put differently: it’s hard to get around the theme of alliance, and it is through alliance that one can grasp the composition of the heterogeneous. It’s true that this theme can be completely empty or purely invocatory, if the alliance is imagined as a pure aggregation of the disparate, without any unifying trait conceived as such; if it is not unified by an object, a horizon, that is, if it does not carry a supplementary political hypothesis. The disaster of the radical militant world is to have become incapable of placing such hypotheses in discussion, hence as working hypotheses, except in the most casual way. It has learned so well to deconstruct its dogmatism, it has incorporated the irreducible plurality of the “terrains” of struggle and the forms of life so thoroughly that it seems panicked by the idea of bearing anything remotely resembling a new will to unification. In this way it aligns itself perfectly with the pragmatist vision of the world, without understanding that the latter is precisely what enables its enemy to maintain its victory.

I’ll simply indicate here, so as not stick with pure invocation, that a political hypothesis capable of binding together completely disparate situations and forms of struggle might be extrapolated from Jason Moore’s analyses of the putting to work of natural beings, which enable us to better see, retrospectively, the cohesiveness of the processes of the economy-world and its destructiveness of natural milieus and their inhabitants — the force driving the destruction of wild species as well as pandemics and climate disruption, but also the putting to work of all the world’s peoples. Work is not a “realized abstraction,” it corresponds to the ensemble of concrete apparatuses which are just as concrete in their appropriation of “free” activity as work when that activity is taken into the circuits of capital’s valorization (marketing of data). Work coercion and the appropriation of free activity as work are the focus of operations of control and subjective suture to the economic order. For capital also has its unwritten laws. The most important among them concerns the desirability of work: it is a law, in the space of capitalism, that one exists there only by occupying a position in the labor market — or more generally, one exists there as a productive subject. Work, in capitalism, is the name of subjectivation for capital. Whence the question raised now by remote work, which has to do with an advance in the indiscernibility between work and life. The capture of subjective dispositions will be irreversible when this indiscernibility itself becomes desirable as such.

A few years ago it was cool in certain militant circles to show that one had gone beyond the “old concepts,” among which that of labor. Perhaps this dépassement can itself be dépassé now. To me it seems possible to return to Marx, or Tronti, by recalling that the struggle against capitalism is a struggle against economic development as such, that is (by adjoining Jason Moore to them) against the putting to work of all natural beings for capital. Not so much to aim for “degrowth,” which too often remains an ethical proposition of no great consequence, as to aim at the heart of the enemy. Perhaps an image will convey the sense of the idea to be deployed: when we revolt we are not workers, but wild animals whose territory is being reduced every day. But the problem is not to go from class struggles to territorial struggles; the problem is that of wilding the class struggle itself. That classes haven’t disappeared, I mean classes as operators of political subjectivation, is also what this crisis management has shown: not only because the poorest people in the globalized space were the most exposed, but also because the only important movement during this period, around Black Lives Matter, was also an expression of this reality of classes. If one grants that, one is perhaps prepared to draw the right line of division. But that line, after having been blotted out, is constantly being obscured again by a state of the world that seems to leave no choice between the forces of capital anchored in the most abject forms of reaction. Layers of confusion keep being piled one upon another, at different scales, insisting that we choose the least worse against the truly worse, but in every case, one only knows that the choice itself is just one more degree in our alienation.

It would be necessary, then, to envisage a strictly political supplement added to the spaces of ethical consistency. One will agree that without ethical substance, politics remains purely formal. But this ethical substance, always necessarily limited, needs to be supplemented. Here the writers of the Manifesto might suspect a last dodge to delay the moment for leaping into the radical decision they propose. A decision meaning that the only question, the only urgency, would be to organize the disengagement from everything that’s organizing the new space of human law. A radical work of separation without any dialectical articulation.

Let’s salute a final aspect of the book: at the heart of the Manifesto’s delivery, there is the demand that one not lie to oneself. The question is whether the search for dialectical articulations is part of the lie. I don’t think so, but it’s definitely something that should be discussed before anything else. It’s true that this would suppose that the holders of adverse positions accept speaking to each other beyond the game of reciprocal accusations, unfounded judgements, and rivalries by which the radical milieu in particular, such as it is, gives itself the illusion of being alive.

First published in Terrestres, September 29, 2022

Translated by Robert Hurley

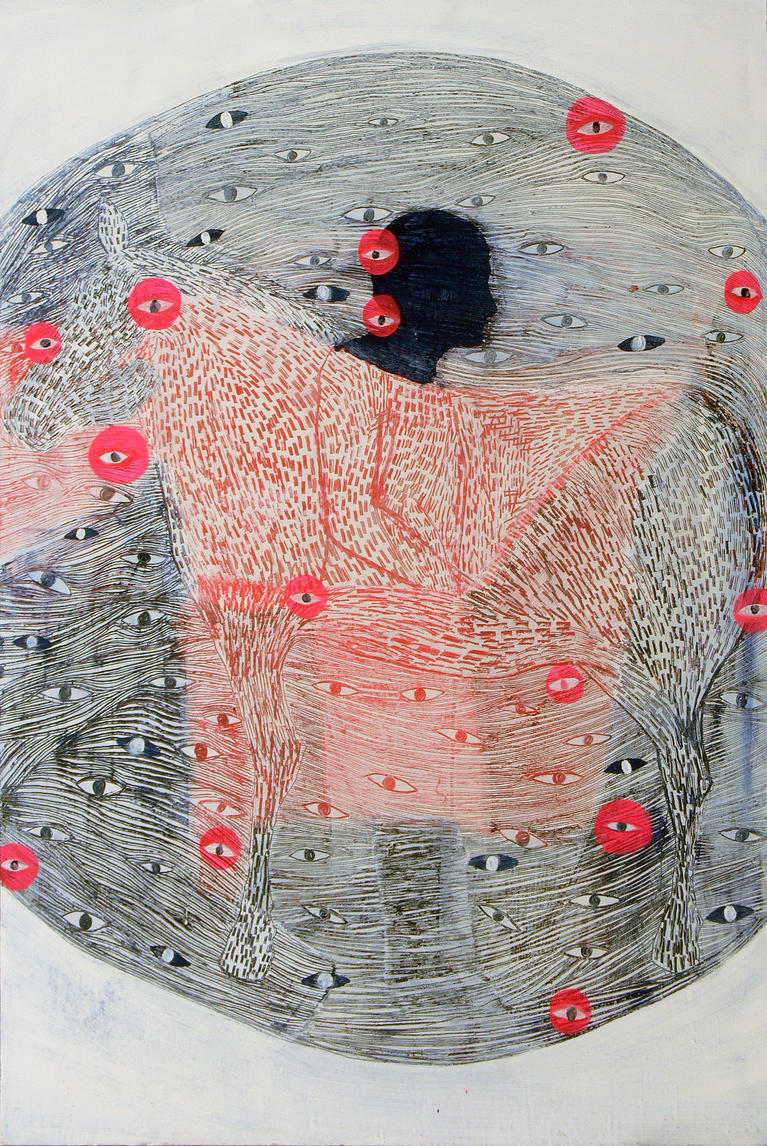

Images: Alexandra Duprez

Notes

1. Surveiller et punir, Gallimard, 1975, 34.↰

2. See Michel Foucault, Naissance de la biopolitique, Seuil-Gallimard, 2004; and Grégoire Chamayou, La Société ingouvernable, La Fabrique, 2018.↰

3. If I speak here of “technocapitalist domination,” it’s in thinking of what Tronti says: the workers movement was the one chance to civilize technology, but that chance is gone. See Mario Tronti, Nous opéraïstes, L’Éclat, 2013, 120-121. ↰

4. Let’s say the form of the “messianic,” particularly in the sense given to the term by Agamben in The Time that Remains, Trans. Patricia Dailey, Stanford, 2005.↰

5. La politique au crépuscule, L’Éclat, 2000 98.↰

6. See Agamben, Homo sacer, Le pouvoir souverain et la vie nue, Seuil, 1995.↰

7. Blinde Passagiere: Die Corona-Crise und ihre Folgen, Kunstmann, 2022. An interview in English with the author about his book is available online on the Endnotes website. ↰

8. See the article by Nathalia Passarinho, Les leçons de la favela de Maré. Online here. My thanks to Denis Paillard for having suggested this article. ↰